I like watching Anthony Magnabosco. His YouTube channel contains hundreds of interviews he’s held with people on their deeply held beliefs, and why they hold them. Each time, it becomes apparent the things they regard as ‘true’ are on pretty shaky ground.

This has ominous implications, as of course the things we hold to be true influence how we treat others, how we vote, and so on.

In a recent video with other deep thinkers however, Anthony went so far as to suggest that faith should be considered a mental disorder. And this is where we part company.

I realize Anthony was probably referring to religious faith (he’s an atheist). Regardless, I think he misses the point: Faith isn’t a problem, but the degree to which we rely upon it is.

Good question, suspicious child.

For me, faith simply means believing in something we cannot prove. Or put another way, if you don’t have proof, but you still believe it’s true, that’s faith.

This seems to at least come close to how a lot of people define faith in their talks with Anthony. Often when they feel boxed into a corner, they fall back on: ‘It’s just what I believe. I have faith.’

In fact, I believe EVERYTHING we think we know is ultimately based on faith.

The Child's 'Why?'

Here’s a relatable example: Your child has just reached that age where they have to know everything in the known universe… And then some. This results in every explanation being met with the inevitable question, “why?”

We can endure a few of these, but eventually (probably because we didn’t actually know the answer), we throw up our hands and say, “go ask your mother/father!”

It’s actually pretty profound, when you think of it. Each successive ‘why?’ forces us to peel back another layer of our understanding – and it quickly becomes apparent that we don’t know the thing nearly as well as we thought.

Consider that we could play the ‘why?’ game with anyone, but even Stephen Hawking himself would have to eventually admit he didn’t know the ultimate stuff that makes everything do what it does.

It’s a terrifying prospect: We don’t actually know how anything works, even the really obvious stuff, like gravity. We’ve got tons of theories and fancy names like ‘gravity wells’ and the like, but why things function that way… That’s a head-scratcher.

This doesn’t mean that we should burn down our laboratories and join the nearest cult however. While we may not know something to be True (with a capital “T”), most of us get by through a combination of faith and evidence.

Faith vs Evidence

Let’s take a quick trip back to grade-school, shall we?

For the non-scientists in the audience, evidence – specifically scientific evidence – is any information that supports a theory of how something works.

The strength of evidence depends on whether it meets certain scientific criteria, like whether it can be reproduced with different people, how free it is from bias, how well other factors that might skew results are controlled, and so on.

So the stronger the evidence, the closer it is likely to be to Truth, and the more we can rely on it to remain consistent.

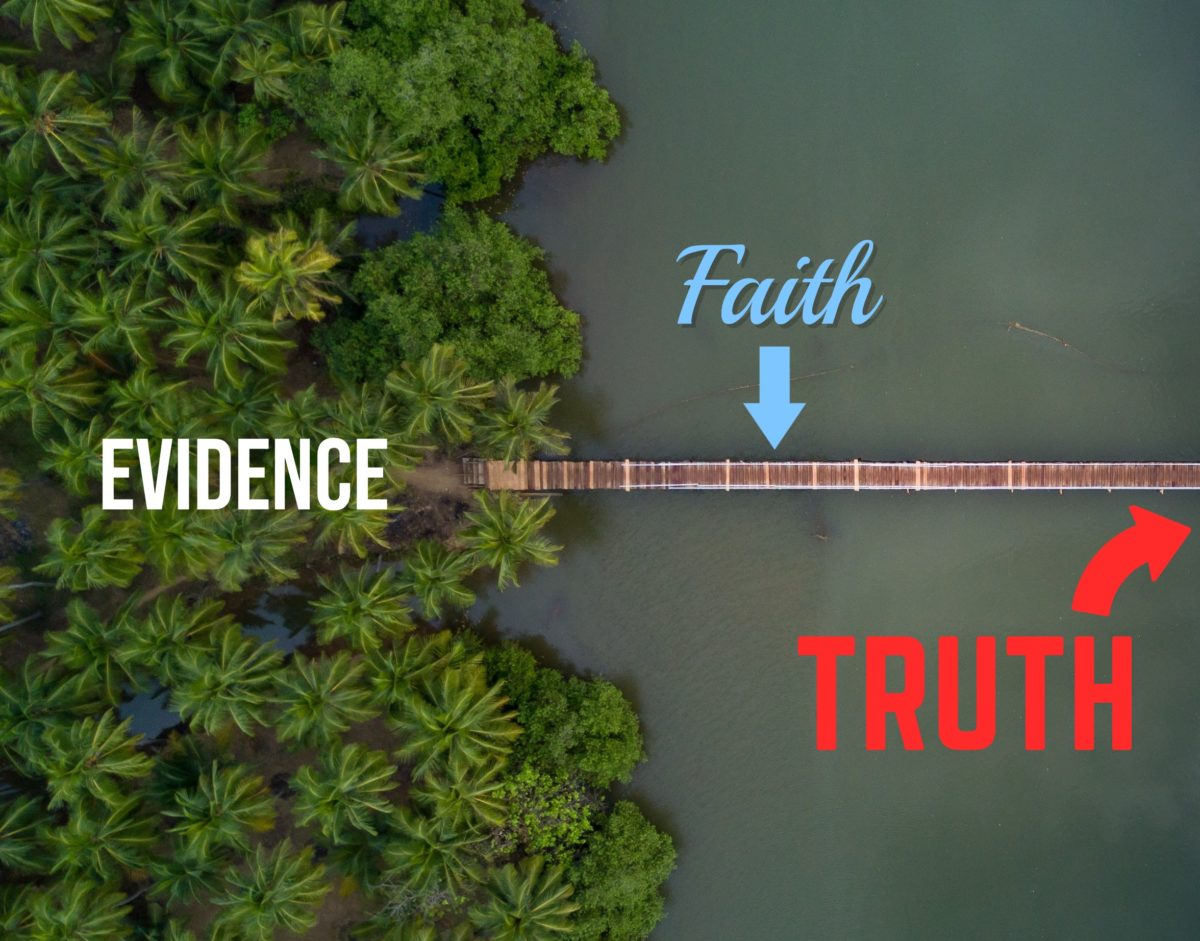

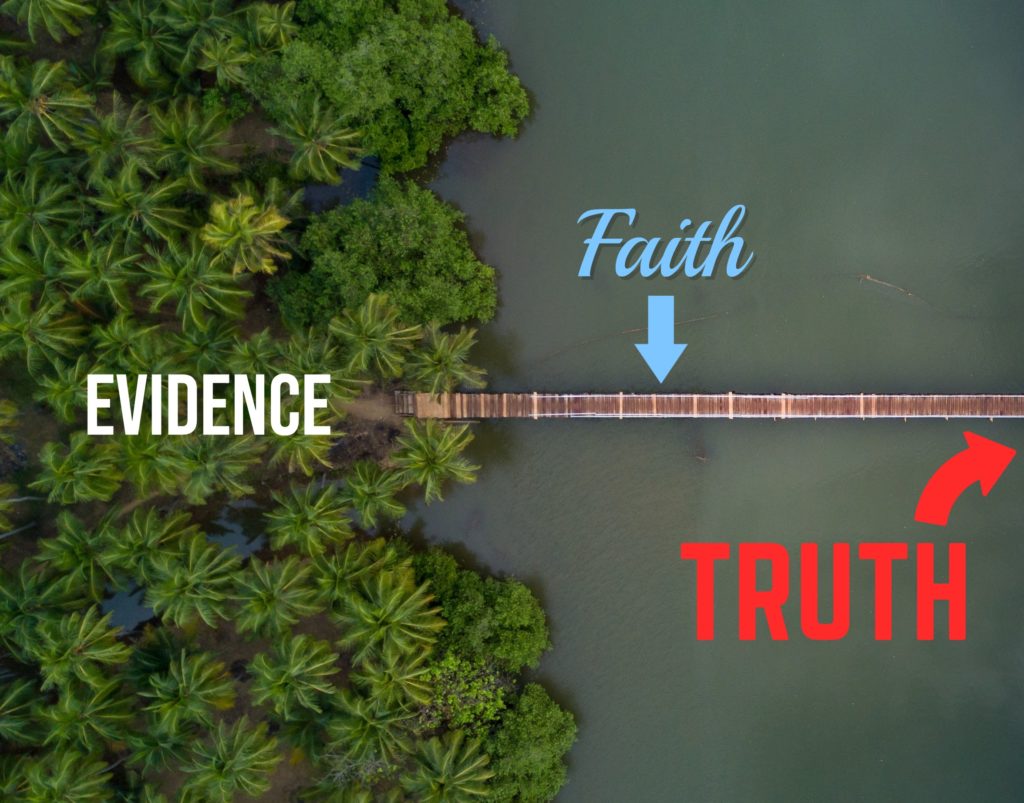

Now, at the beginning of this article, I used an image of a bridge over a river, with the ground representing ‘evidence’, and the bridge denoting ‘faith’. Here it is again:

Because scientific evidence fulfills certain real-world criteria, we might say it is relatively ‘solid’, like the ground in this picture. BUT, as we mentioned earlier, it only goes so far towards Truth.

The remaining gap (the bridge) must be filled with faith. Without it, you wouldn’t be able to trust ANYTHING to stay consistent – you would worry constantly about whether the sun would rise, or if gravity would cease to function.

Now, I’m going to express a controversial opinion: I believe that faith can potentially get us closer to Truth than evidence, in the same way that our subconscious can provide us with valuable insight that would never have occurred to us otherwise.

But the serious drawback is that it’s next to impossible to be sure of the reliability of our beliefs. Like Schrödinger’s Cat, we can’t be sure it’s alive or dead without looking in the box.

This isn’t to blast the reliability of faith, per se – it’s that our predispositions usually bury our more subtle intuitions, which end up distorting the message. Here’s a few ways we do this:

1.

Childhood biases and trauma. As part of growing up, we all learned certain things about the world, and our place in it. These – sometimes painful – lessons have become so ingrained in us over the years, we may not even know we still follow them.

2.

Expectation bias. When we want something to be true, we often rationalize our experiences until it seems true to us. Seriously, I’ve been REALLY sure of some things, until I got another perspective and realized I was being slightly crazy.

3.

Peer pressure. Often we are part of a group that believes similar things, so we unconsciously resist anything that might cause us to believe differently.

4.

Personal virtue. The need to be perceived (by ourselves and others) as a good person is something we all share. Naturally, we will strongly resist anything that seems to challenge that.

Scientific evidence tries to counter these kinds of biases, so it tends to be more reliable. Faith (as far as I know) is less protected against these influences, so it’s more like a narrow bridge – it can get you there, or it may drop you into the river.

I’m sure there are people who know themselves well enough to filter the out the neurotic crap from their inner messages. I’ve yet to meet one however.

So, what can we conclude from all this? We need faith to have confidence in our decisions and the world around us. But in practice, it’s a bit of a rickety tool.

For me, the only compromise that makes sense is to fill in the river. The more solid ground (evidence), we have, the narrower the gap that needs to be bridged with faith, and therefore the less likely we will get pulled off course.

I guess what I’m saying is, believe what feels right to believe, but don’t use faith and belief as a substitute for evidence. Ever heard about the man who jumped from a building, believing he could fly? It didn’t end well.

And on a final note, I just want to be clear that this wasn’t a veiled attempt to take a jab at religion. Rather, like Anthony, I want to see us get as close to the Truth as possible. It will be a better world when we do.

Credits:

Aerial Photography of Brown Wooden Footbridge Connecting Two Forests’ by Guduru Ajay bhargav from Pexels

‘An Orange Tabby Cat Lying in a Cardboard Box’ by Arina Krasnikova from Pexels

‘Boy in Yellow Button Up Shirt Standing Near Wall’ by Anna Shvets from Pexels

‘Tired female student lying on book in library’ by Andrea Piacquadio from Pexels

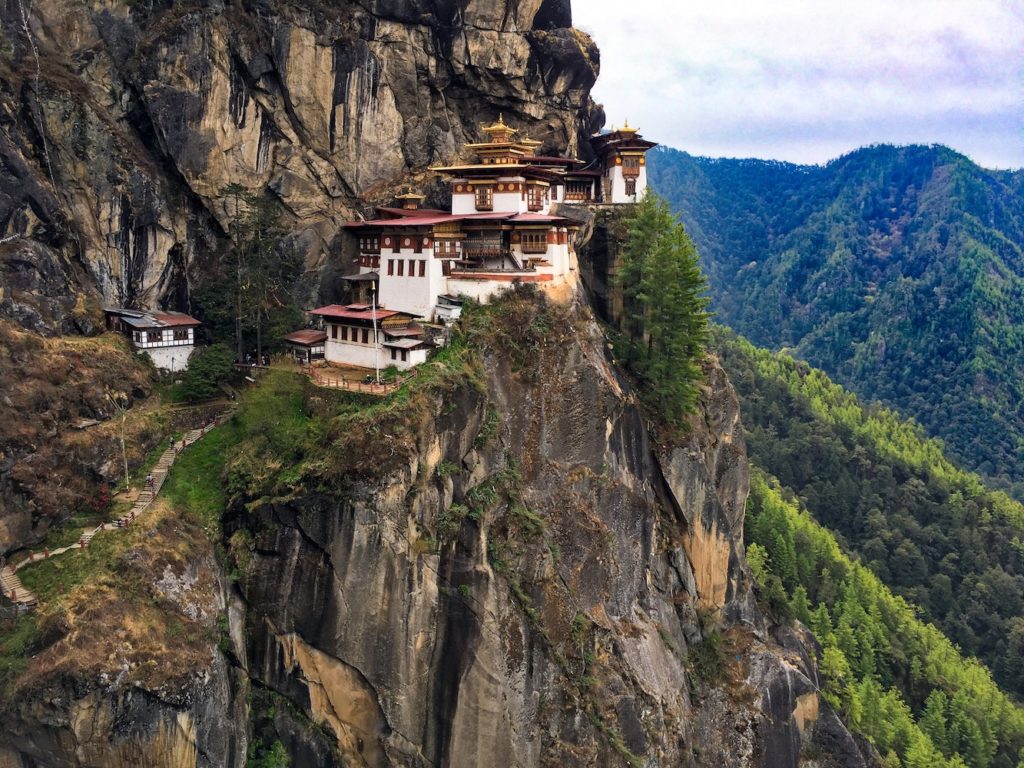

‘White, Black, and Brown House Beside Moutantiasn’ by Peng Lim from Pexels